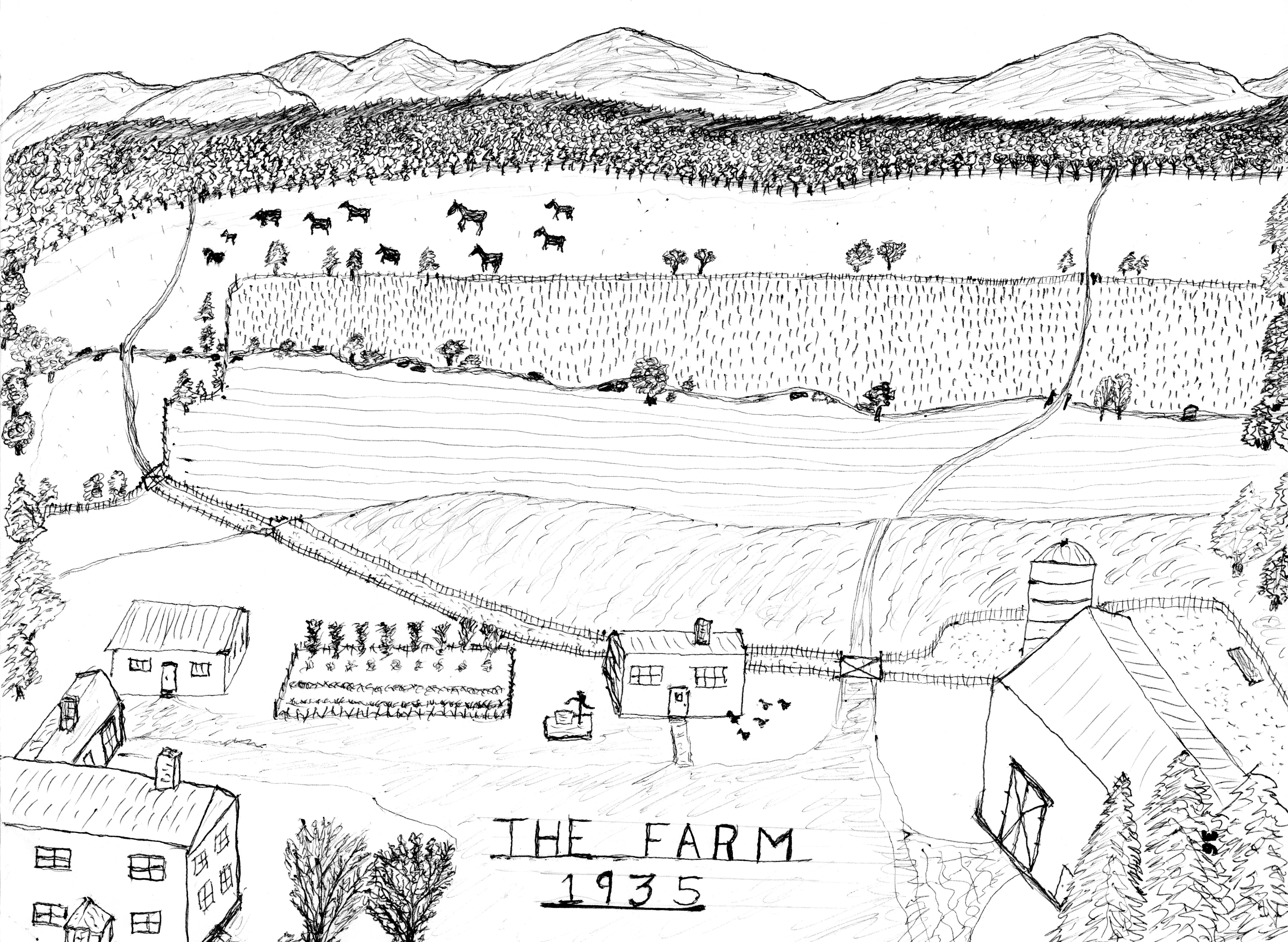

Chapter Eight

LIFE ON THE FARM

Four Seasons, All Work and Little Play

by Richard Poulin

Our grandfather, Michael Poulin, came down from Canada to New Haven and bought a farm on South Street in 1888. The farm was about 120 acres, half was tillable land and the other half was pastureland and woodland. It was a farm that could handle about thirty cattle and was equipped with modern machinery for that time, some of it going back to 1880. There was a set of plows, harrows, a two-row cultivator, a mowing machine, a dump rake and a corn harvester and a combine. We had a wagon, we had a buggy and we had three horses.

Life on the farm was hard and you put in long hours. You got up in the morning generally about quarter to five and you worked until about six at night and sometimes a little bit later, because some things you had to finish that day.

When we boys were old enough to handle jobs on the farm, we would feed the calves and feed the pigs. And we'd throw down the ensilage for the cattle and as we got older we were allowed to milk the cows.

I'm going to start this story on January first early in the morning when there's deep snow on the ground and it's cold outside. Dad would get up in the morning and light the lamp and go downstairs and check the stove in the living room to see if there were coals left and throw on kindling and a chunk of wood and then he would go into the kitchen and start a fire in the kitchen stove. Then he'd take his lantern, light it, and go out to the barn and hang it on a hook and milk the cows. After he'd milked, he'd feed them ensilage and then he'd come in and have his breakfast and then he'd go out and feed the cows and horses their hay.

The first thing we kids would do when we came downstairs was look at the windows to see what Jack Frost had painted during the night. Of course then we didn't have storm windows and the frost would be on the inside of the window and sometimes the snow would blow through the cracks and be there in the morning on the window sill.

In every season there were certain jobs you had to do. Wintertime was when you got up the woodpile. That meant going up into the woods, cutting down the trees, sawing them up into lengths that would fit the sleigh, then bringing it down and piling it up somewhere near the woodshed. Later it would be sawed up into chunks suitable for splitting for the stoves.

We also got up wood to use in the sugar house. You cut that a year in advance and let it dry a year to make sure you would have a nice hot fire under your evaporator.

Another job in the wintertime was to get in the ice for the ice house. Generally, you had to wait fairly late in January when the ice had gotten to about eighteen inches thick. We got our ice from Allen's Pond. Our icehouse was near the barns and the milkshed and sawdust was used for insulation. You'd bring the ice in on a sleigh and place it on a thick layer of sawdust. You'd leave a 12 inch space around the sides of the building to be filled with sawdust. Then you'd bring in the first cakes of ice, lay them on a layer of sawdust and between successive layers you'd put a thin layer of snow so the second layer wouldn't stick to the first and so on. On top, you'd put one or two feet of sawdust. You planned to store enough ice to cool your milk through the summer.

Sometimes in winter the snow would get so high and drifted into the roads that it was impossible to get through even with a sleigh, and what we would do was take down the neighbor's fence and drive the team through his meadow until we could get back on the road again. The farmer didn't mind as long as you put his fence up again.

Another thing we did in the wintertime between other jobs was hitch up our sleigh and go to the manure pile and spread manure out on the fields for fertilizer.

Along about the first of March, the weather started getting warm and it was time to think about sugaring. We would go to the sugar woods up above the pasture and drill a hole in a maple tree, hammering a spout in the hole and hanging a bucket on it. You might hang one bucket, two buckets or three buckets depending on the size of the tree.

After you got your buckets hung on the trees you'd go back to the sugar house and get set up to make sugar, and put your gathering tank on the sleigh.

The best weather for sap to run was warm days and cool nights. After a cool night when the day warmed, you'd see sap running into the buckets and it would have been running most of the night. Next day you'd take your sleigh with the gathering tank and go around and empty the buckets and when the tank was full you'd drive back to the sugar house and transfer the sap into a storage tank from which you'd draw sap for the evaporator.

You had to be good at heating the sap to make sure it didn't get too low and burn the bottom of the pan -- then you were in real trouble. Or if you didn't watch, it might boil over and you'd have a mess. What you did a lot of times was hang a piece of pork on a long string and let it hang over the evaporator just low enough so it would be below the rim of the pan so when your sap started boiling and rising and hit that pork it would settle right down again.

We also made maple sugar at our house. I don't know how many gallons we made but I know there were three grades -- there was Fancy, Grade A and Grade B. Along toward the end of the season you'd start making Grade B which is a poorer grade but has more maple flavor to it. Mom made the maple sugar in the back kitchen where we had another wood stove. We'd boil it down to the right density for sugar and put it up in 5 gallon cans, labeled and ready for sale.

After the sugaring and when you had your firewood all in, it was getting along toward spring and time to start mending the fences. The ground was too soft to get on with farm equipment so you'd hook up the wagon, take some wire and some staples and follow your fence line where the wire had come down in the winter months or where the fence posts had loosened. Then you would tighten those down.

As soon as the work was done on the fences and the land had dried out, you could start plowing. After plowing you would harrow the land; then you would smooth it, plant your corn, plant your oats and plant your wheat.

Along about the first week in June the hay would be high enough to start cutting. I never really looked forward to haying; we didn't have the modern machinery. We had a mowing machine and a dump rake which was operated by hand. We'd start at one end of the field and when your tines were full of hay you'd trip it with a foot pedal and continue along, making successive trips, then return, tripping loads on the same line so when finished you'd have continuous lines of hay.

Then you "tumbled" the hay into little piles that could be lifted onto a hay wagon.

You didn't throw it on the wagon any old way or it would fall off before you reached the barn. You put the first two bundles on the corners of the wagon and put one in between the two to bind them on. You continued in this way to lock your whole load in and that way when you got to the barn you'd generally arrive with your whole load of hay.

At the barn we had a hay fork. A boy would lead the horse and the rope would pull the fork and the hay up to the track at the top of the barn and over to the mow where you would trip it and down would come the hay.

When you weren't haying you had to take time to cultivate your corn. We had a two-row cultivator. You'd steer it with your feet and you'd have to be mighty careful or you'd tear up your corn.

We always planted lots of potatoes. Everybody had a potato bin down in the cellar. We put up enough potatoes to last all winter long. Of course they had to be hoed. They had to be tilled.

As soon as haying was over it was time to think about thrashing. This was a neighborhood project because not everyone owned a thrasher. We used to have that done. The neighbors would come with their teams of horses and we'd thrash away in the forenoon while the ladies got up a big meal and we'd all eat and go back to thrashing.

After they finished at one farm they'd go on to another and the same neighbors would help out and also enjoy a big meal.

Filling the silo with chopped corn for the cows in winter was much like thrashing. The neighbors would assist, then the machinery and workers would move on to the next farm.

After winter, spring and summer tasks are done, it's time to move on to fall. Now we're getting colder weather and start to think about butchering the pigs and getting up the meat for winter. We used to say we saved every part of the pig but the squeal. We had a smokehouse and would smoke the hams. Mom made "boudain," blood sausage, that was a favorite with the older French folk but not with us youngsters.

Also in the fall we'd pick berries and crabapples and all the produce from the orchard and garden for canning and storage for the winter.

I don't want to forget the cider. We had a good-sized orchard and in the fall we'd pick the apples, sort them, put them in barrels and ship them. The apples that were second grade would be sent to the cider mill and we would get two barrels of cider. Our neighbors had cider too.

We didn't use all our cider for vinegar, either. When we had company Dad would say, "Boys, go down in the cellar and get a pitcher of cider." We could draw it out of the barrel using the spigot at the bottom or use a syphon hose up at the top. We preferred that method because you could always get a couple of extra sips that way.

Dad came home one day and said the bank had closed and that was the start of the Great Depression. But I guess us farmers were better off than a lot of folks. We had our gardens and Mom put up a lot of canned goods and we had vegetables and jams and plenty of potatoes. We had plenty to eat.

The only thing we were short of was cash and us boys found ways to earn a little by helping neighbors, picking walnuts and butternuts and getting a few coons and skunks and selling their hides.

This would be the end of the farming year and tomorrow Dad would get up and do the same things all over again.

All of this is true. This is the end of my story and I hope it was informative. I'll probably be thinking of things I should have said but at the moment they didn't happen to come to mind.